Do Female Athletes Get ACL Injuries Because Of Hormones?

By Emily R Pappas, MS

Research demonstrates females are 3-6x more likely to experience an ACL injury compared to male athletes…..but are our hormones to blame?

Are female’s innately more fragile? Or is there much more to the story we need to consider….

This article helps explain the current SCIENCE explaining the relationship between female hormones and injury risks.

Have you seen this before? Maybe on a vintage-looking poster or printed on a miniature porcelain head in Target.

It’s a phrenology chart.

You probably walk by them all the time at Urban Outfitters or Crate&Barrel. This an old science illustration turned into a quirky coffee table decorative.

It’s a little ironic. You see, back in the 1800s, phrenology was a serious business.

At the time science was trying to understand what makes people different. Why are there differences between men and women, poor and rich, religions and races?

The problem is, they only focused on obvious physical differences. They hadn’t really thought about ‘nurture vs. nature’, how economic and educational opportunities could change someone’s life.

Phrenology was a horribly one-sided attempt to neatly categorize humans.

How did it work? Basically, scientists of the day proposed this theory:

You could tell someone’s personality, intelligence, and even future potential…all by mapping out the measurements and different bumps on their head.

It seems pretty harmless; especially in an era where those same scientists used cocaine to cure hayfever and arsenic to treat psoriasis.

But in today’s world, using bumps on your skull to define WHO you seem pretty crazy, right?

But in trying to understand the complexities of what makes us different…phrenology did a lot of very real harm. Measuring the bumps on people’s heads became the basis for systematic racism, sexism, and was used to as a “fact-based” excuse for inequality.

If anything, those little porcelain heads remind us science has bumped its own head as it’s stumbled along the path to modern medicine.

But things like phrenology charts are a cautionary tale.

Why?

Because we are still working to understand the human body.

And, we’re still hitting our own bumps along the way. “Old science” and its missteps are comedic “What the heck were they THINKING?!?” stories in hindsight.

But what happens when a mistake becomes widely accepted? What happens when that belief leads to people getting hurt?

That’s the heart of what we’re challenging today: how our understanding of sex hormones, or male vs. female hormones, contribute to ACL injuries.

And how our previous misunderstandings are continuing to hurt female athletes.

It’s Not Black And White.

In Victorian times, if you were considering marriage, you might ask your potential partner for a mapping or “reading” of their skull.

Why?

So you had a “scientific” read on whether it was a good match. Phrenologists claimed they could tell you if your true love had a capacity for compassion, how secretive they were, and if they were able to enjoy life.

The problem is…phrenologists were looking for a “black and white” solution to something that isn’t that easy.

In the same way, medical specialists, nutritionists, coaches, and sports scientists have…in the recent past…pointed to hormones as the major variable in predicting ACL injury risks.

And why wouldn’t we?

Published and peer-reviewed studies report things like:

“While more physically active males injure their anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) due to their greater exposure to high-risk sports activity, high school and college-age females are 2-5x more likely to suffer from a non-contact ACL injury compared to similarly trained males” (6)

And

“This increased risk in females occurs around 13-14 years of age when females begin to markedly differ from females in hormone secretion and their physical characteristics such as body composition, joint laxity, and hip and knee control” (6)

These studies focus on men vs. women…and sex hormones underlie most of our physical, post-puberty differences.

Hormones do make a difference.

“Female” sex hormones have the potential to impact the STRUCTURE of your ACL…think things like

collagen metabolism,

ligament remodeling,

and structural integrity

In theory, this all makes sense.

Hormones must be the culprit!

Afterall:

Females have higher levels of estradiol compared to men, and we know this hormone effects collagen metabolism and ligament laxity…

… we also know knee laxity increases when estrogen levels rise during certain phases of the menstrual cycle…

Since knee laxity is linked to ACL injury risk, it makes sense female athletes are more likely to experience non-contact ACL injuries.

THE END!

But far from giving us clarity, this kind of “black and white” thinking only clouds our effort to understand what’s really going on. We start to ask questions like…

…do “female” sex hormones make women inherently weaker?

…does just being a female put us at a higher risk for injury?

….are we at higher risk of injury during certain times of our hormonal cycle?

It’s NOT THAT BLACK AND WHITE.

Sex hormones are complex. They vary widely athlete to athlete.

And, most important for this conversation, their role is just one part of a larger system.

Cyclical hormones vary so widely athlete to athlete, period to period, and are so widely variable that makes it difficult to establish a “baseline” or control for studies on normal hormone cycles might correlate to injury.

Then, consider contradicting studies on female athletes with non-regular or depressed hormone cycles.

“Female athletes who demonstrate menstrual cycle disturbances (and depressed sex hormone concentrations and fluctuations) report a greater percentage of severe musculoskeletal injuries than athletes with normal menses (8).”

MEANING females who have LOWER levels of endogenous sex hormones actually show HIGHER rates of musculoskeletal injuries.

Maybe just having female hormones- being a female athlete- isn’t really the cause of injury after all.

Could there be something else we aren’t considering? Is there another variable actually putting us at risk for ACL injuries?

Read on.

Weak In The Knees: Girls Vs. Boys In ACL Injuries

“Greater risks of anterior knee laxity are associated with greater risks of an ACL injury” (6)

First, what is knee laxity?

The short answer: It’s how much movement you have in your knee.

Anterior knee laxity is how much displacement happens between the tibia and femur when an anteriorly directed load is applied to the posterior tibia.

Check out the changes in this athletes knee displacement as she runs!

Another view of anterior knee displacement that naturally occurs in running/ sprint mechanics

Before puberty, the laxity of the knee is pretty much the same (on average) between boys and girls.

But when athletes mature during and after puberty, females generally maintain a higher laxity while it generally decreases in males.

This means, on average women, have a greater movement range than men throughout their athletic career.

But the words “in general” should be a red flag for anyone looking at the science. Women have a HUGE degree of variance, person to person. And, to complicate this even more, not all women have greater knee laxity than men.

So, does this really mean hormones are to blame?

Or could there be another factor, something in her lifestyle or evolutionary history, that is the root of a woman’s knee laxity?

Or maybe both?

Female Athletes Experience Constant Changes In Knee Laxity

One of the reasons it is so difficult to really blame ACL injuries on hormones alone is the ever-changing amount of laxity a female athlete experiences.

A woman’s knee laxity is not constant.

“Laxity is greater on average in the periovulatory days of the cycle (high hormone) and to a lesser extent the mid-luteal days. (1)”

These changes were observed on average 3-4 days following changes in sex hormone concentrations. Even more, these changes were more pronounced in those females who had LOWER minimum estradiol and higher minimum progesterone concentration. (6)

Why is this important?

Two things:

#1. Greater knee laxity = Higher Injury Risk

Those who experience greater acute increases in knee laxity are more likely to move toward higher risk biomechanics when knee laxity is increased (1)

Basically, if your baseline knee laxity is already high, when you enter into parts of your cycle that may increase knee laxity- you’re at risk of injury. Your body is more likely to have

Knee stiffness when landing

Greater dynamic knee movement and forces during landing and cutting

#2. If your baseline hormones are altered because of birth control…you could also be at higher risk.

“Increasing estradiol concentrations have the potential to influence collagen synthesis and ligament integrity in a dose-dependent and negative manner (5)”

Last I checked, there aren’t a lot of male athletes using hormonal contraceptives.

And, as it turns out, hormones (our own and those we put in our body with oral contraceptives) play a BIG role in how your body builds and maintains soft tissue.

Especially during puberty, when your body is developing tissues and bone mass.

We talk about how oral contraceptives aren’t a cure-all here in this article.

You see hormones, particularly estrogen, play a direct role in soft tissue metabolic activity.

On average, higher levels of estrogen are associated with a

Decrease in collagen

Decrease in protein

Decrease in fiber diameter and density

These effects might be temporary, only lasting during a certain part of your period. But they are super important when we start talking about ACL injuries in women vs. male athletes.

Why?

Collagen is the main load-bearing structure of the ACL ligament!

Evidence suggests sex hormones can influence your collagen metabolism and the structural integrity of your ACL.

It makes sense. Especially since receptors for important sex hormones (such as estrogen and relaxin receptors) are present on the ACL.

Lets talk: RELAXIN

Those of us who have never been pregnant probably haven’t heard much about relaxin outside of a side-mention in our 6th-grade health class.

That’s because relaxin is a hormone traditionally considered a pregnancy hormone. It’s the hormone that relaxes the pelvic floor in preparation for labor.

But even if you aren’t pregnant, you still have relaxin in your body.

And its receptors?

You guessed it…you can find them on your ACL.

Females tend to have a higher number of relaxin receptors on their ACL compared to males, and young females show higher amounts compared to adult females. (5)

With this higher presence, scientists have postulated that higher serum concentrations of relaxin are responsible for a greater incidence of ACL injuries in female athletes. (2)

In a retrospective study in 2011 (3), Division 1 female athletes who suffered from an ACL injury revealed 3x higher levels of relaxin as well as more cyclical variability throughout her cycle.

Other retrospective work (2) has indicated both serum relaxin and knee laxity values were significantly higher in females with a history of ACL injury compared to control.

Sounds convincing right? Relaxin is the culprit!

Here’s the thing: these studies COMPLETELY ignore how relaxin levels fluctuate during menstrual cycle phases and menstrual irregularities.

This is a critical factor in female athletes: almost 50% of exercising females experience menstrual and therefore hormonal irregularities (7).

In a study (1) performed on eumenorrheic collegiate female athletes (females who regularly menstruate every 21-35 days), no difference was observed between mean relaxin levels compared to male controls. Although significant variances were observed in serum relaxin levels over a 4 week period, there was no significant difference in knee laxity measured by anterior translation.

In a meta-analysis performed in 2006 (8), 6 out of 9 studies on female athletes reported no significant effect of the menstrual cycle and ACL laxity.

Even more, the majority of these studies that did find a relationship between the menstrual cycle and ACL laxity based their findings on a single sample day of the cycle (without any hormonal confirmation of cycle phase). This approach makes the assumption that all days within a cycle represent an equitable hormone environment.

Quite frankly, we ALL know women experience hormonal fluctuations.

Here is the thing: Estrogen & Relaxin do not act alone, they are part of a much greater system.

This potentially disastrous effect of estrogen and soft tissue metabolism is attenuated (decreased) when progesterone and/ or testosterone is present. (6)

Guess what: Testosterone and Progesterone also FLUCTUATE with estrogen and relaxin throughout a female’s cycle…. And with every cycle, these fluctuations can be different.

So does that mean a female is at a higher risk of injury during certain phases of her cycle? Would controlling that cycle, through hormonal contraceptives, help reduce risk?

There are THREE BIG QUESTIONS we need to ask as we figure out what is really behind all the ACL injuries.

Question #1: Is An Athlete More At Risk For ACL Injury On Her Period?

Some retrospective studies on ACL injury risk suggest there is a relationship between the injury and what time it happens during the hormonal cycle.

In general, a greater number of injuries reportedly occurs during the follicular phase (stage one) compared to ovulatory (1)

Here is the problem:

Some studies (1) showed a greater frequency of injuries occurring in the early follicular stage (premenstrual) = lowest hormonal environments

Some studies (6) showed greater frequency in the late follicular phase nearing the rise of estrogen and ovulation

Some studies (3 )showed greater frequency in the post-ovulatory phase

If these injuries were as directly correlated to our hormones as we thought, why wouldn’t the majority of these injuries occur during times when estrogen was the highest?

A bigger concern is also the question:

Are females so sensitive that a specific hormonal environment may make participation in sport at certain times unsafe?

But that isn’t all. The studies themselves have another big issue…they depend on self-recall.

That means they are counting on those athletes to accurately remember exactly where she was in her cycle when she was injured. To add to this mess, remember cycles are not the same for all women. The truth is, in these studies we don’t actually know the hormonal milieu of the athlete before and during the injury.

This chart shows just how different, person to person, fluctuations can be:

Graph taken from the text “Sex Hormones, Exercise, and Women”

In this diagram, you can see 4 women with 28-day cycles (6). This is a very simple representation. Still, you can see EACH woman had different times when her estrogen peaked, her progesterone peaked, her testosterone peaked, and when she ovulated.

So are females actually at a higher risk for an ACL injury during their “follicular or pre-ovulatory phase”?

Or are we assuming athletes are in this phase without actually knowing their hormone environment?

Of the studies in the 2006 meta-analysis (8) that did show an association between ACL laxity and the menstrual cycle, all three found laxity increased during the post-ovulatory phases of the cycle (the post-ovulatory phase has a much higher peak of progesterone and a smaller peak of estrogen compared to the preovulatory phase)

That means…these findings on ACL laxity DO NOT coincide with the majority of published findings that cite females experience more ACL injuries during their pre-ovulatory to ovulatory phases of the menstrual cycle (1)

If Estrogen and relaxin PEAK in the pre-ovulatory phase, why does laxity increase during the POST-ovulatory phase?

And why do more injuries occur when laxity is reportedly lower?

There are a number of reasons…

We don’t really know how the specific mechanisms through which sex hormones are actually impacting soft tissues and the potential for ligament failure work

Women have varied in hormonal levels. This could mean SOME women demonstrate large alterations in laxity through the cycle…while others demonstrate little to none (2)

Changes in hormone concentrations that depend on the cycle may not consistently influence knee laxity

It is possible more injuries occur when the ACL ligament is STIFF rather than lax

Hormonal effects on injury rates may be more neuromuscular than structurally related.

Athletes who experience menstrual irregularities and the consequence of those hormonal disruptions is really at the heart of the study

There are too many variables. Too many things that could explain a possible correlation, and not enough to make the theory stick.

So MAYBE, just maybe, females aren’t as fragile as initially thought.

Current science is starting to conclude what us female athletes have felt all along:

It is HIGHLY unlikely that any negative effect on soft tissues is due to a single hormone, but rather represents a complex interaction among multiple hormones and other relevant factors such as the individual’s genotypic profile and exercise habits. (6)

Basically, you can’t generalize what is going on as a consequence of being female. Male and females all have different genetics, are in different sports, and train at different intensities.

All of these factors may describe the extent to which a female athlete is susceptible to an ACL injury!

Question #2: If A Female Athlete Stops Having Her Period, What Does That Mean ACL Injury Risk?

When we think the menstrual cycle, we think hormones right?

So when you think “menstrual cycle disturbance” think fewer hormones…or more specifically a lack of the cyclical concentration of these hormones.

The reason studying menstrual cycle disturbances is important in the ACL debate is that abnormal menstrual function (or menstrual dysfunction) is reported to be as high as 50% of exercising females. (7)

When we say “menstrual dysfunction”, that can mean:

Oligomenorrhea or menstrual irregularity (9 or fewer cycles per year)

Primary Amenorrhea (not having your period by age 16)

Secondary Amenorrhea (not menstruating for 3 or more months in the absence of pregancy or lactation)

Theoretically, if estrogen and relaxin are the cause of ACL injuries in female athletes, athletes who demonstrate menstrual irregularities should, therefore, have lower concentration of these hormones and lower injury rates right?

NOPE.

The opposite is true.

Some research (4) suggests that the risk for severe musculoskeletal injury may be somewhat higher in high school females athletes who experience menstrual cycle disturbances or with primary amenorrhea.

In a study on high school female athletes in 2012 (4), researchers cited females who experienced menstrual irregularities (9 or fewer cycles) were almost 3x as likely to sustain a musculoskeletal injury compared to athletes reporting normal menses.

Remember, sex hormones work together and do more than just prepare your body for reproduction!

Estrogen plays a critical part in bone formation. We talked about that here this article.

The more time spent without adequate estrogen levels during growth for female athletes, the lower their peak bone mass and lifetime bone density. Studies have repeatedly shown how irregular menstrual cycles are associated with stress fractures. (3)

But what about the ACL?

There aren’t a lot of studies on this.

In these handful of studies (3), a significant relationship exists between musculoskeletal injuries (including ACL injuries) low bone mineral density, oligomenorrhea/ amenorrhea/ and low energy availability.

What does this mean?

Your history of menstrual disturbance is likely to increase your injury risk.

You see, it isn’t the hormones causing the problem. It’s the depression of hormones.

With the new ASCM position on REDs, and current research on the subject (7), it is likely that low energy availability is the confounding factor when considering the cause of high ACL injury rates in female athletes. .

Even more if nutrition is inadqeuate, female athletes who sustain a musculoskeletal injury such as an ACL injury may also negatively impact their tissues ability to rebuild (5).

So if low sex hormones, caused by not getting enough calories, places female athletes at a higher risk for ACL injuries…what happens if you take hormones from an oral contraceptive?

Question #3: Can Birth Control Lower ACL Injury Risk?

Here, we explain how oral contraceptives (OCs) are an outside hormone supply to your body…and why that matters.

If estrogen and relaxin really contribute to higher ACL rates in female athletes, taking an oral contraceptive pill that reduces these levels should result in lower ACL injury rates…..right…?

The results of a 2019 systematic review of the literature (7) suggest the plausible association between OCPs and ACL injuries are not so black and white.

Of the seven studies examining the effects of OCs on the incidence of soft tissue injuries, only two concluded that OCs decrease the risk of ACL injuries, while four found OCs to have no effect on ACL injury risks. One study even determined that OCs could increase the risk of developing Achilles tendinopathy.

Additionally, one study (5) observed no group differences in knee laxity and OCs, while another observed lower knee laxity in OC users.

Various types of OCs have also been reported (5) to actually result in HIGHER concentrations of markers of collagen synthesis and degradation.

Other studies have shown that women using OCs showed reduced collagen production and smaller tendon fibril diameters.

With the belief of elevated levels of relaxin being associated with increased ACL injury rates in female athletes…it would make sense that OCs, which inhibit ovulation and relaxin levels, decrease ACL injury risks, right??

In a study that compared progestin-only pills with combined pills (4), there was no statistically significant difference between ovulation suppression and ACL injury risk.

Why ALL the different findings?

It is possible these findings are inconsistent because there are SO MANY variations in the oral contraceptives themselves.

So…can hormonal birth control help reduce the risk of an ACL injury?

To date, there is no strong evidence that oral contraceptives protect from ACL injuries. (5)

In these studies, there are just too many outlying factors: differing hormonal profiles, type of OCP used (monophasic, triphasic), duration of use, the purpose for use (primary amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea).

It is possible OCs may serve a therapeutic role in “decreasing sex disparity” in ACL injury rates (4) but we need more research.

What we do know is that taking an oral contraceptive is definitely not going to help influence LOW ENERGY AVAILABILITY…which we KNOW is an underlying problem of a majority of menstrual irregularities in female athletes.

What Does This Mean For Us Girls?

The human body is complex.

As our understanding of it grows, our perspectives also evolve. We once thought the relationship between women’s hormones and ACL injuries was black and white.

Now, we’re seeing the problem isn’t that simple to solve. There are many factors that might play into WHY females are experiencing ACL injuries at such greater rates than males.

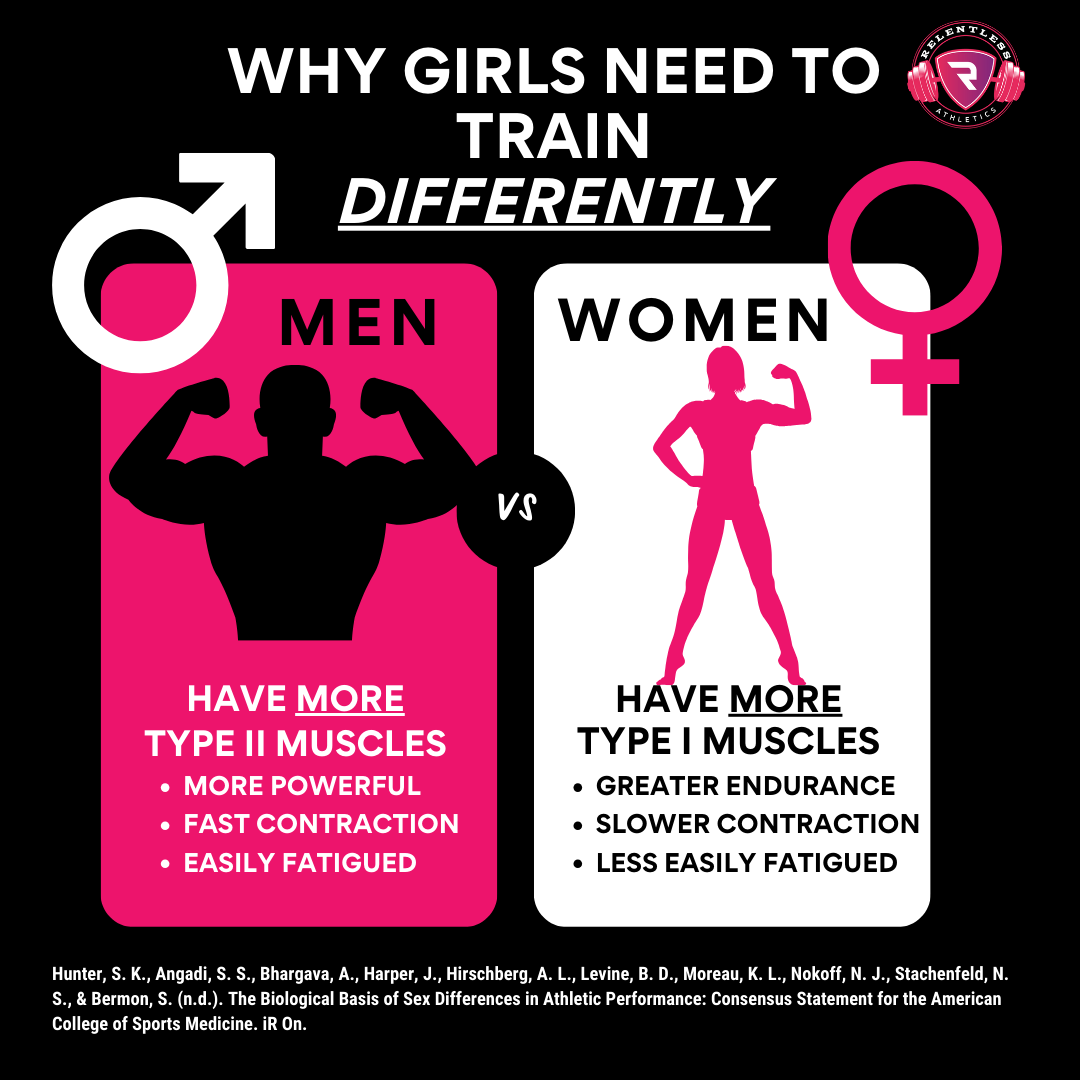

Before we start villainizing female hormones for the cause of this “sex disparity”, it may make more sense to look at other differences between male and female athletes that go BEYOND hormones.

With this in mind, it’s time to consider if higher knee laxity is biological…or environmental.

Or, in the phrenological debate…is it nature causing these ACL injuries, or nurture?

Tools and training, especially strength training, have been shown to decrease injury risk in all athletes. But to date, most female athletes are not provided these tools to the same degree as male athletes.

In fact, research at the high school level (9) cites 50% of male athletes being required to engage in strength training, while less then 10% of female athletes are required.

Hopefully, as we empower girls to hit the weight room in between soccer practice, we’ll see the male/female gap in injury rates close.

And, if it turns out hormones really do put female athletes at a higher risk, doesn’t doing all we can to train to reduce our chance of injury just make sense?

References

1.Anderson, Michael J., et al. “A Systematic Summary of Systematic Reviews on the Topic of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 4, no. 3, 2016, p. 232596711663407., doi:10.1177/2325967116634074.

2. Arnold, Christopher, et al. “Relationship of Serum Relaxin Levels to Knee Joint Laxity in Female Athletes.” Relaxin 2000, 2001, pp. 437–439., doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2877-5_72.

3.Dragoo JL, Castillo TN, Braun HJ, Ridley BA, Kennedy AC, Golish Sr. Prospective correlation between serum relaxin concentration and anterior cruciate ligament tears among elite collegiate female athletes. AM J Sports Med. 2011a; 39(10): 2175-80

4.Konopka, Jaclyn A., et al. “Effect of Oral Contraceptives on Soft Tissue Injury Risk, Soft Tissue Laxity, and Muscle Strength: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 7, no. 3, 2019, p. 232596711983106., doi:10.1177/2325967119831061.

5.Rauh, Mitchell J, et al. “Relationships among Injury and Disordered Eating, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Low Bone Mineral Density in High School Athletes: a Prospective Study.” Journal of Athletic Training, The National Athletic Trainers’ Association, Inc, 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20446837.

6.Shultz, Sandra. “The Effect of Sex Hormones on Ligament Structure, Joint Stability and ACL Injury Risk .” SEX HORMONES, EXERCISE AND WOMEN: Scientific and Clinical Aspects, SPRINGER, 2018, pp. 113–138.

7.Thein-Nissenbaum, Jill M., et al. “Menstrual Irregularity and Musculoskeletal Injury in Female High School Athletes.” Journal of Athletic Training, vol. 47, no. 1, 2012, pp. 74–82., doi:10.4085/1062-6050-47.1.74.

8.Zazulak, Bohdanna T, et al. “The Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Anterior Knee Laxity.” Sports Medicine, vol. 36, no. 10, 2006, pp. 847–862., doi:10.2165/00007256-200636100-00004.

9.Reynolds ML, Ransdell LB, Lucas SM, Petlichkoff LM, and Gao Y. An examination of current practices and gender differences in strength and conditioning in a sample of varsity high school athletic programs. J Strength Cond Res 26: 174-183, 2012.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emily holds a M.S. in Exercise Physiology from Temple University and a B.S. in Biological Sciences from Drexel University. Through this education, Emily values her ability to coach athletes with a perspective that is grounded in biomechanics and human physiology. Outside of the classroom, Emily has experience coaching and programming at the Division I Collegiate Level working as an assistant strength coach for an internship with Temple University’s Women’s Rugby team.

In addition, Emily holds her USAW Sport Performance certification and values her ability to coach athletes using “Olympic” Weightlifting. Emily is extremely passionate about the sport of Weightlifting, not only for the competitive nature of the sport, but also for the application of the lifts as a tool in the strength field. Through these lifts, Emily has been able to develop athletes that range from grade school athletes to nationally ranked athletes in sports such as lacrosse, field hockey, and weightlifting.

Emily is also an adjunct at Temple University, instructing a course on the development of female athletes.