It needs to be said: “playing your sport is NOT ENOUGH to avoid detraining during the sports season”.

By Emily Pappas, MS

When sport seasons start, many female athletes stray away from the weight room as sport practices and games take over their schedules. The result: DETRAINING.

“But how can my athlete detrain when she is PLAYING her sport?”

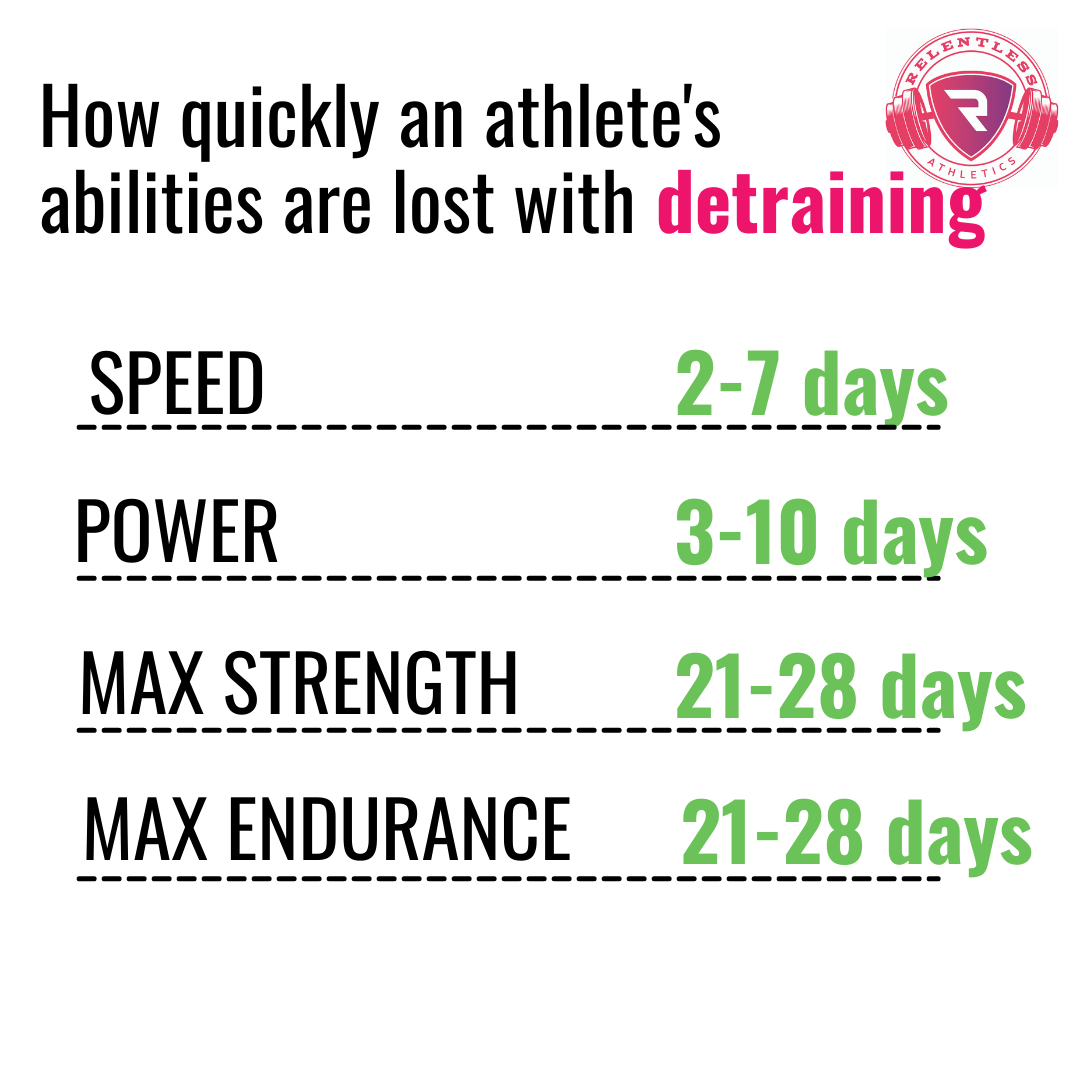

It is simple, playing sports is NOT ENOUGH to maintain improvements realized outside of the season. In fact, after 3-4 weeks away from the weight room, all of the benefits your athlete realized begin to DECREASE and return to BASELINE.

Avoiding this detraining effect is easy, but it is important to understand why maintenance training is necessary if you want your athlete to maintain her speed, power, and avoid injury during her competitive sports season…..

Training OUTSIDE of the competitive season

When an athlete is outside of her most competitive season, she is able to realize increased strength, power, speed all while reducing injury risks through a progressively overloaded resistance training program.

This type of program will function to stress the body with a particular stimulus, introduce back off or de-load periods, and help your athlete realize adaptations that promote enhanced performance [4].

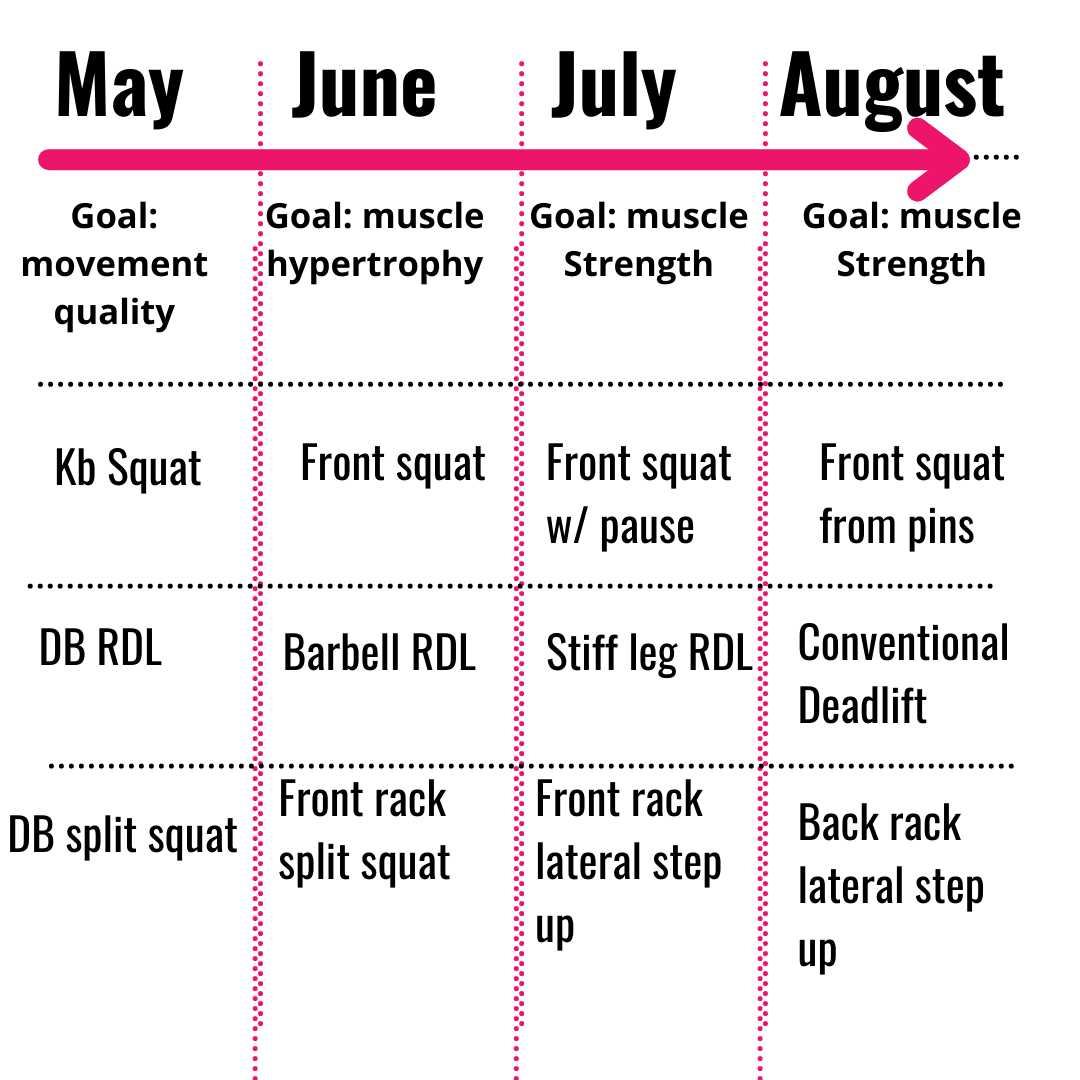

To give you an example, let’s say you want your athlete to sprint faster in her field hockey game while helping ensure her knees stay injury free.

During the Summer, her training program should encompass lower body movements that are progressed both in volume, intensity, and movement type to allow for increased muscle mass, tendon capacity, strength and power outputs.

The goal of training during this period should be

Acquire skill of movement

Perform movement at higher volumes (and promote muscle growth)

Continue muscle growth and increase loading for increased strength

Continue to drive strength leading to lower reps, higher intensities, and decreased time constraints for power production

This is a very simple example of what this progression should look like for bilateral knee dominant movements, unilateral knee dominant movements, and bilateral hinge movement patters…..all functioning to promote lower body strength to allow for increased speeds & decreased injury risks come September when the field hockey season starts.

What to do once the sport season starts.

For MANY female athletes, with busy schedules and school starting, the weight room gets pushed to the sideline. At this point the athlete feels strong and whatever nagging pains that were left over from last year are gone…..

So what is the issue? The athlete is playing her sport so that will keep her strong, right? WRONG.

This is because SPORT is a completely different stimulus along the ABSOLUTE STRENGTH to ABSOLUTE SPEED continuum.

When an athlete is in the weight room, she is developing ABSOLUTE STRENGTH (as well as power and strength speed as she advances)

Research demonstrates ABSOLUTE STRENGTH drives ABSOLUTE SPEED. Meaning, the STRONGER an athlete is, the FASTER she is.

Unfortunately the converse is not true. Working on SPEED does NOT enhance strength. Unfortunately all sport games & practice are either SPEED (or often times turn into an endurance workout…. but thats for another article)

This is an issue as not only does STRENGTH drive improved performance, but strength training has been shown to reduce injury risks by 50% [8]!

When an athlete removes strength training from her schedule, she removes the stimulus that helps her MAINTAIN A HIGH TOP SPEED and also HELPS HER STAY OFF THE SIDELINE due to injury.

Why? Because after 3-4 weeks without strength training, the female athlete DETRAINS.

This means as the athlete’s season continues, she will REVERSE the benefits her previous training imposed. As a result the athlete will realize

less strength

slower top speeds

less power

and an increased chance of injury.

You see playing her sport 6 days a week is great to keep her SPORT skills high, but it is NOT GREAT at keeping her strong, powerful, and INJURY FREE.

If an athlete continues to stop resistance training, once play-offs hit, she will be at her LOWEST PHYSICAL LEVEL

This means all the work & benefits she put in PRIOR to her season will NO LONGER EXIST.

How to avoid detraining?

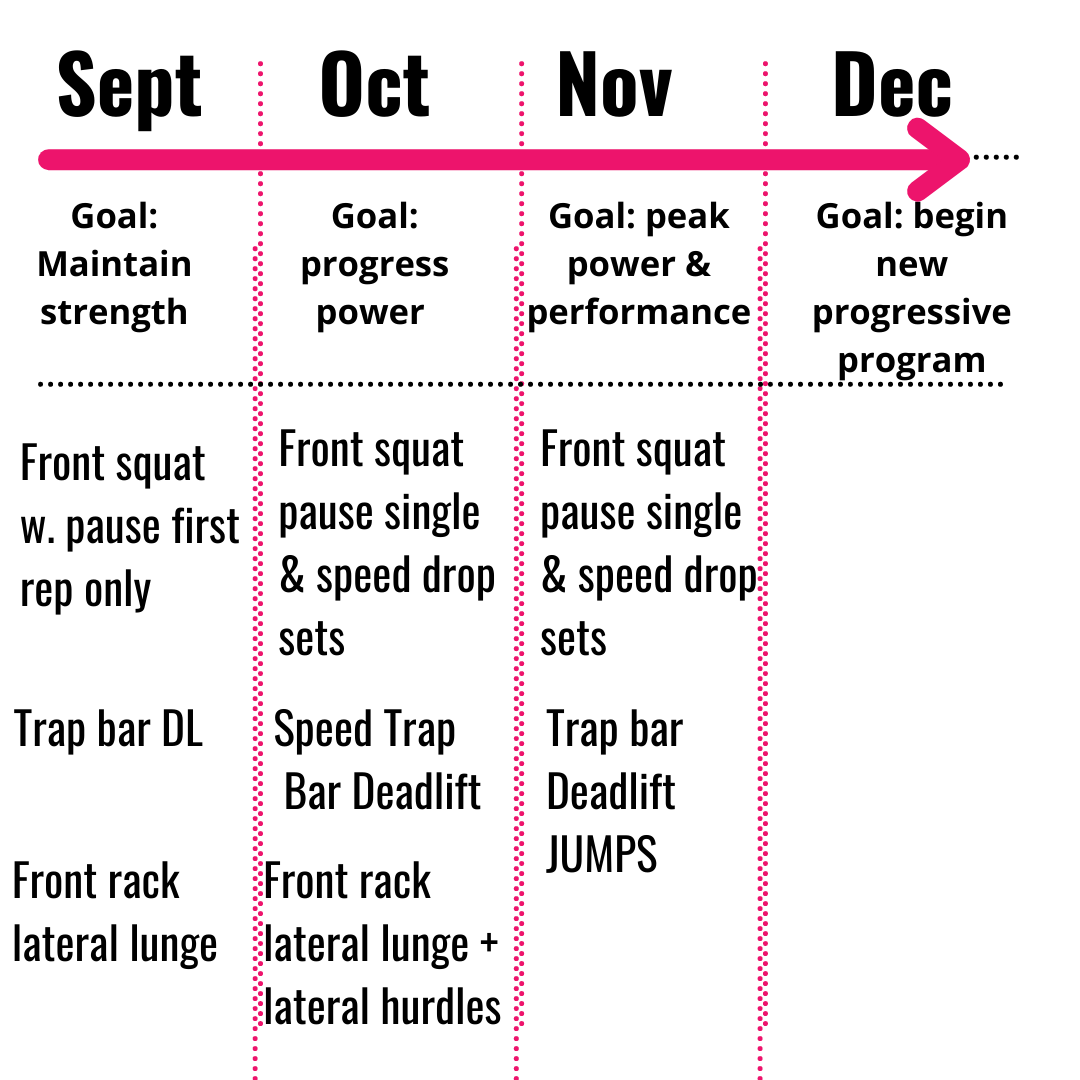

During the season, the goals of the resistance training program must convert from PERFORMANCE ENHANCEMENT to PERFORMANCE MAINTENANCE.

This type of training consists of [3,5,7]

Lower volumes

Higher intensities

as this type of training allows for REDUCED FATIGUE and increased power outputs….all while providing the stimulus needed to REDUCE INJURY RISKS

Strength training should be maintained at a minimum of 1x/ wk at 45-60min to avoid detraining.

For example, during the Fall he program for the field hockey athlete looking to peak her speed & keep her knees healthy needs to encompass higher intensity and lower volume movements introduced in per previous training.

The goal of training during this period should be [3,5]

Maintain Strength

Progress Power

Peak power & performance

Mitigate Fatigue

This is a very simple example of what this progression should look like for progressing her bilateral knee dominant movements, unilateral knee dominant movements, and bilateral hinge movement patters…..all functioning to maintain in season performance

To further maximize recovery and reduce injury risks, this period of time must also EMPHASIZE RECOVERY [10]

sleeping 8-10 hours per night

eating 4-6 servings of protein per day

Research has repeatedly demonstrated female athletes who focus on MAINTENANCE during their season have: [8]

higher peak performances near the end of their season (playoffs)

lower incidence of injury

are able to build upon their previous improvements once season ends

If you want these benefits, female athletes need only 45-60min of resistance training PER WEEK during the season (which typically lasts 2-3 months)

Managing Busy Schedules & Lifting

When you understand the importance of lifting during the season, the next question is HOW to make it work?

Often school practices/ games are 5-6 days per week at 2-3 hours each [insert eye roll]…

We get it, it is ALOT. But scheduling one session before or after a game or practice is not only ok, but highly recommended!!!

This is because of the body’s immense ability to adapt!

In fact, your athlete should have already been exposing her body to higher volumes of training BEFORE season started to be able to handle this (such as 4x per week lifting + sprint training & skill work)

As season hits, think the total volume of training she is exposing her body to should stay around the same, but be MORE sport and LESS lifting.

Why is this recommended? Well, research suggests athletes who perform the BEST and are the MOST RESILIENT to injuries maintain a HIGH TRAINING LOAD year round, but the ratio of what contributes to the training load differs. [4]

As long as your athlete is taking one rest day per week, consuming enough protein & carbs to meet her body’s needs, and lifting minimum 1x per week during the season, she is on the road to success & an injury-free season.

Rest assured if you are holding your athlete out of the weight room fearing it is TOO MUCH for her body to handle during her sport season, you are actually putting her at HIGHER RISK of injury and a poorer performance this season.

REFERENCES

Colby MJ, Dawson B, Peeling P, et al. Repeated exposure to established high risk workload scenarios improves non-contact injury prediction in Elite Australian footballers. Int J Sports Physiol Perform2018;15:1–22.

Fulton, Jessica et al. “Injury risk is altered by previous injury: a systematic review of the literature and presentation of causative neuromuscular factors.” International journal of sports physical therapy vol. 9,5 (2014): 583-95.

Gabbett TJ, Hulin BT. Activity and recovery cycles and skill involvements of successful and unsuccessful elite rugby league teams: a longitudinal analysis of evolutionary changes in National Rugby League match-play. J Sports Sci2018;36:180–90.

Gabbett TJ. Debunking the myths about training load, injury and performance: empirical evidence, hot topics and recommendations for practitioners J Sports Med Published Online First: 26 October 2018. Doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099784

Gabbett, Tim J. “The Training—Injury Prevention Paradox: Should Athletes Be Training Smarterandharder?” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 50, no. 5, 2016, pp. 273–280., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788.

Harrison PW, Johnston RD. Relationship between training load, tness, and injury over an Australian Rules Football Preseason. J Strength Cond Res2017;31:2686–93.

Kalkhoven, Judd Tyler, et al. “A Conceptual Model and Detailed Framework for Stress-Related, Strain-Related, and Overuse Athletic Injury.” 2019, doi:10.31236/osf.io/vzxga.

Lauersen, Jeppe Bo, et al. “Strength Training as Superior, Dose-Dependent and Safe Prevention of Acute and Overuse Sports Injuries: a Systematic Review, Qualitative Analysis and Meta-Analysis.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 52, no. 24, 2018, pp. 1557–1563., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099078.

Malone, Shane, et al. “Can the Workload–Injury Relationship Be Moderated by Improved Strength, Speed and Repeated-Sprint Qualities?” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol. 22, no. 1, 2019, pp. 29–34., doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.01.010.

Milewski MD, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, et al. Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. J Pediatr Orthop2014;34:129–33.